Forensic anthropologist

Forensic anthropologists examine human skeletal remains for law enforcement agencies to help with the recovery of human remains, determine the identity of unidentified human remains, interpret trauma, and estimate time since death.[1] Forensic anthropology is a subfield of anthropology (the study of humans).[2] To conduct all the research and analyze of the bones forensic anthropologists use specialized tools such as a mass spectrometry, forensic radiology, etc. [3] The history of forensic anthropology goes back to the 1800s and continues as a profession today. [4] Forensic anthropologists needed to fight for the popularity it now has, but it also gained some popularity through crime shows. Due to this spike in popularity the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that 21 percent of employment growth will happen to forensic anthropologists from 2010 to 2020.[5]

Job Description

Forensic anthropologists work mainly with bones and use osteology in their work, which is the study of bones. Using this study and their extensive knowledge on the topic of human remains, forensic anthropologists also assist the government and federal cases which include the remains of a human. Working with law enforcement, forensic anthropologists help them determine whether the death was a homicide, suicide, accident, or even a natural disaster. Forensic anthropologists also analyze the culture in which any victim once lived in allowing them to understand more about their background and childhood. Not only do they assist the government in murder cases, but they also help uncover bodies after natural disasters by identifying the remains and finding the family. [6] While working with government on cases with a murder victim, or such, forensic anthropologists are also called during the trial of the case to provide their notes of the victim. [2]

History

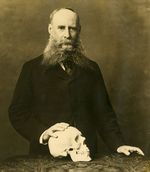

The history of forensic anthropology dates back to the 1800s with a man named Thomas Dwight (1843-1911). Dwight is credited as the Father of Forensic Anthropology in the United States because of the many things he did for forensic anthropology and popularizing it as well. Dwight was also the first person to write and provide lecture on the study. He published many methods to aid identifying human remains (i.e. sex was found from the joints by long bones). An original case using forensic anthropology was in 1849 and the remains found belonged to Parkman. Two professors working at Harvard at the time, Oliver Wendell Holmes I and Jeffries Wyman, were asked to assist in determining the identities and any other clues that would help unearth the murderer. While there were more murder cases in this time they were not popularized, meaning forensic anthropology was still obscure to other people. Authors such as Harris H Wilder and Brent Wentworth published books about how to identify human remains and how to create a facial reconstruction, which were used by other forensic anthropologists.[4]

However, a turning point in popularizing forensic anthropology was during World War II and the Korean War. First, in World War II the bodies of soldiers were only growing quickly in numbers. To resolve their problem the U.S. Army Office created the Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii (CILHI), where directors identified the remains of human soldiers. One director, Mildred Totter (1899-1991), began to improve the way of identification of human remains, using only the bones. Totter assisted in the advance in the study and practice of forensic anthropology. A second turning point in the advancement in forensic anthropology was during the Korean War, and a similar crisis arose again. During this war the bodies of soldiers continued to rise and as a resolution they created another Identification Laboratory in Japan. With T. Dale Stewart was the director and many colleagues worked with him. However one colleague, Thomas McKern wrote an article with Stewart about methods in identifying the age human remains. Those two events not only helped the discoveries of new methods in forensic anthropology, but also allowed family members of soldiers to receive closure.[4]

Methods

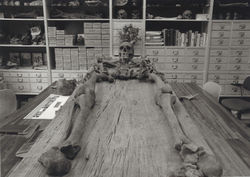

Before a forensic anthropologist may identify bones, there are certain steps that they should follow while attempting to identify bones. The first step, that may be obvious, is to make sure that what they are looking at is bone. The next step follows the first, the forensic anthropologist must determine whether or not the bone is human.[7] For a forensic anthropologist to classify a bone as a bone they must use their knowledge in human osteology.Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; invalid names, e.g. too many Once the forensic anthropologist has identified the bone to be real and human they then identify what bones they are looking at. They do this by laying the bones out on a table in the order of what it is like in a human body. In the process of doing this the forensic anthropologist is able to see if they are missing or have extra bones. For the forensic anthropologist to differentiate between two different bones from different people they may look at size and when the body was killed. Knowing when the bodies were dead allows the law enforcement to know if the victim was murdered recently or not.[7]

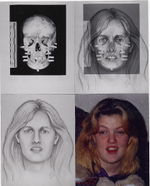

One method that is important, as are other methods, is a facial reconstruction. Facial reconstruction is used whenever the discovered human remains are unidentified, and are created by a sculptor who specializes in facial anatomy, who may also be a forensic artist. Facial reconstruction may also aid in the discovery of new injuries or birth traits of the human remains. Facial reconstruction can go either two ways, one way is a three dimensional reconstruction while the second method used is a two dimensional reconstruction. Three dimensional reconstructions begin with the forensic artist placing tissue markers in certain positions, which are based on the victims age, race, and gender. After the tissue markers are glued the forensic artist then places false eyes in the skull. Once everything is glued the forensic artist begins to use clay and places the clay over the tissue markers until it resembles a face. Then the forensic artist will use specific details about the victim, such as the location the human grew up in. When the forensic artist completes the face they may add hair and other specific details known about the victim. However two dimensional facial reconstructions differ from three dimensional greatly. Two dimensional reconstructions begin with placing tissue markers onto the skull as three dimensional reconstructions, however instead of using clay the forensic artist will photograph the skull with the tissue markers and a ruler placed beside the skull. The photos are then used to assist the forensic artist while sketching the face while using the measurements for the eyes, nose and the mouth. All other details needed for the face are given to the forensic artist from the forensic anthropologist.[8]

Video

This video takes you back to Clyde Snow, a forensic anthropologist, who needed to analyze the bones found under John Gacy's house.

References

- ↑ What is Forensic Anthropology? Forensic Anthropology Center: University of Tennessee. Web. Accessed November 16, 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Forensic Anthropologist Job Description Crime Scene Investigator EDU. Web. Last accessed October 25, 2017. Unknown author.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Historical Background of Forensic Anthropology Cheshire Anthropology. Web. Date of publication January 17, 2017. Unknown author.

- ↑ Ley, Samantha. Job Description of a Forensic Anthropologist Career Trend. Web. Last updated July 5, 2017

- ↑ What is a Forensic Anthropologist Forensic Anthropologist. Web. Last accessed October 25, 2017. Unknown author.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Anthropology Virtual Museum. Web. Last accessed October 8, 2017. Unknown author.

- ↑ Facial Reconstruction Crime Museum. Web. Last accessed October 25, 2017. Unknown author.

| ||||||||||||||||||||